This post contains the final essay in Official Guide: I Have Seen The Future, the third book I created with Johannah. The book purports to be the official guide to the 1964 World’s Fair had it accurately predicted 2022, rather than dreamt up “a great big, beautiful tomorrow.” (E.g., instead of flying cars, our book’s “Transportation Pavilion” boasts a dilapidated Cross Bronx Expressway.) In 2022, the war in Ukraine was well underway but Gaza had yet to be razed. Civilian casualties, I would argue, are the entire point of both wars (indeed, most wars), and something we are not taught enough about in school. I am posting this piece for three reasons: (1) because it is buried deep within a thick, glossy, expensive book (the ultimate paywall); (2) it covers material Johannah and I will be lecturing about at the the Palais de Tokyo in Paris on May 18; and (3) because, aside from mention of the ongoing genocide in Palestine, it feels like I could have written it in the last week or two, during cherry blossom season.

🌸 🌸 🌸

This is a book about inheritance.

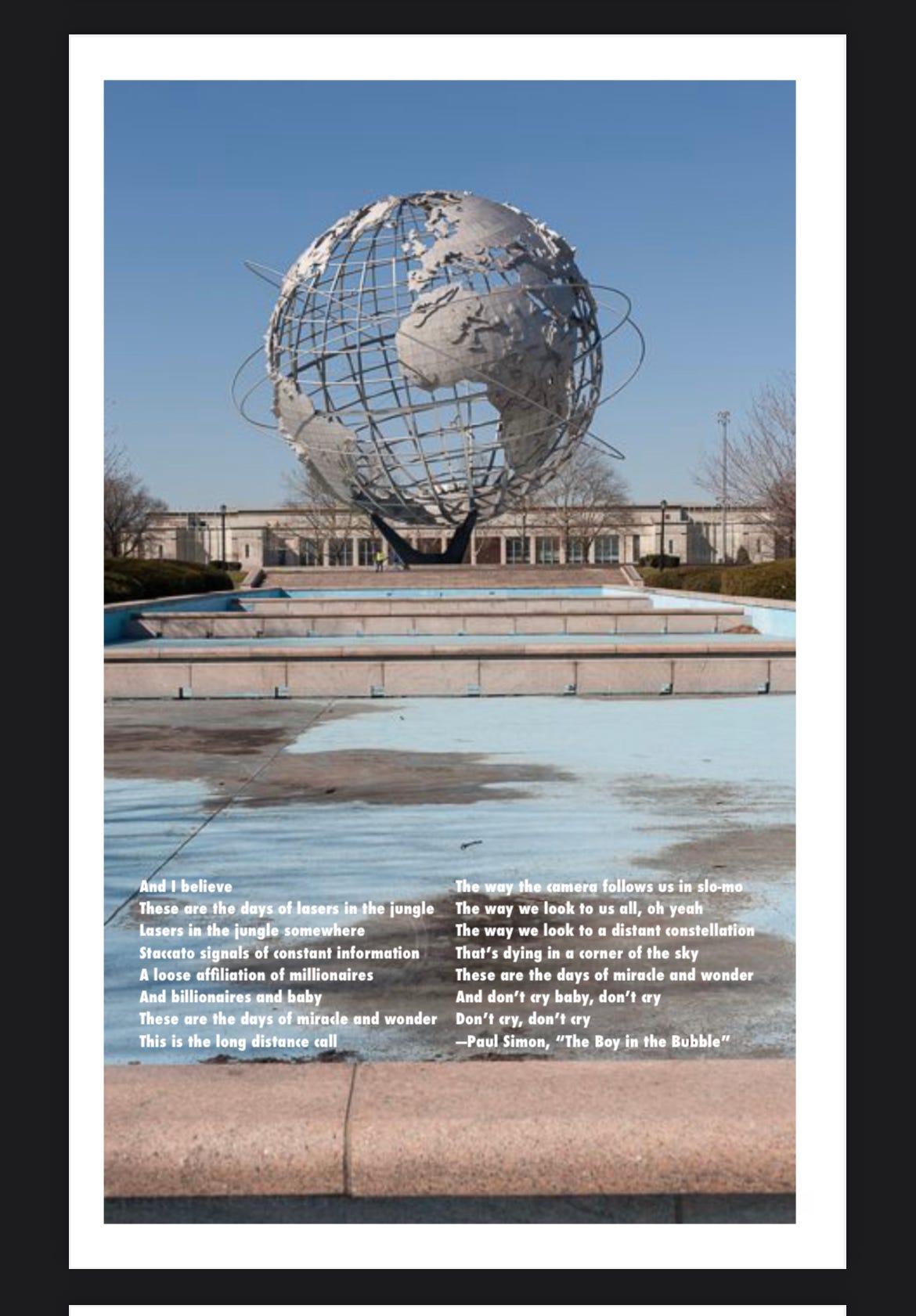

What is a World’s Fair if not someone’s idea of what the next generation ought to inherit? In a sense, it’s utopia by committee. Utopia is a top-down hope foisted on society at large. Utopia is a violence. Utopia is also a parkway, a playground, and a neighborhood in Queens, foisted on New York City by Robert Moses. All of these utopias—as well as Utopia Bagels—are located roughly five miles from the World’s Fair Grounds, another Moses concoction. (N.b., foisted is, in fact, a word of Dutch origin, employed here because it was the Dutch who first foisted Western civilization upon this part of the world and upon the Lenape, but I digress.)

Asking “Who is Robert Moses?” feels an awful lot like asking, “Who is John Galt?” The notion of a Galt gone awry perhaps tracks, not that Galt had a hope of going a-right in the first place—unless you mean ideologically. Imagine: a Republican (or anyone) invested in public works! Except, he wasn’t of course. Rather, he enriched himself through a larcenous public-private partnership at once at the geographical heart of New York City, yet nearly invisible to all: directly beneath the Triborough Bridge. (That bridge is now renamed for Bobby Kennedy who—as perhaps you read earlier in this book—both wiretapped Martin Luther King, Jr. and served as an aide to Sen. Joseph McCarthy.)

Moses’ empire, the Triborough Bridge Authority, was an empire hidden in plain sight. The nefarious scope and vastness of Moses’ power was outed by the brilliant Robert Caro in what has to be the most thoroughly researched character assassination in the English language: The Power Broker. Published in 1973, while Moses was still very much alive, the book is lauded and oft quoted, but many tend to elide the tome’s full title, which reads: The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. It charts the course of a man left to define utopia with a free hand, a love of cars (more than people as it was often charged), and an eye for radical European architecture to sweep away any parts of the city he found inconvenient—and then bury under 627 miles of new road.

The two World’s Fairs that Moses brought to Queens bookended the 25 years of his ascendancy. Each also brought to the fore a world wracked by conflict: the beginnings of the Second World War in 1939 and the height of Cold War tensions in 1964. The 1939 World’s Fair was actually a World’s Fair, sanctioned by a governing body in—pourqoui pas?—Paris. The 1939 fair saw the exclusion of Germany. The fair’s organizers buckled under political pressure from NYC Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in the wake of a 50,000-person Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden in the winter of the same year.

In the middle of the 1939 fair, as war raged, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the USSR were all forced to pack up and leave the slogan of “Peace and Understanding” behind. In 1942, the Trylon and Perisphere, the fair’s iconic structures, were melted down for US armaments. Between the fairs, a stretch of the east side of Midtown—previously known as Blood Alley for all the slaughterhouses therein—was razed to host the United Nations. During construction, the UN Headquarters were housed in what had been the 1939 New York City pavilion and what is now the Queens Museum. Unbelievably, both before and after it served as the UN Headquarters, that building hosted a roller rink—going in circles, indeed.

The 1964 fair was rogue: Moses could not get Paris to approve its mounting in the Big Apple, so they went ahead and threw a renegade one anyway, using mostly corporate funds, hence its far more commercial flavor—the same kind of public-private sector collusion so familiar to Americans today. Tellingly, our foe at the time was excluded: the Soviet Union. The loony, breathless consumerism of the fair was, in fact, wholly intended as a blow against this absent foe, a Kitchen Debate made flesh. That propaganda wasn’t just for the adults with wallets: both fairs notably featured an ongoing entanglement with Walt Disney and his bowdlerized, rather racist cartoon vision for the American Way. The cartoon villain was implicit.

This book is about the world we inherited. Admittedly, it’s an awful lot like 1939, but with the nuclear firepower of 1964. And the villain remains the same. The bitter legacy of brinkmanship is paralysis. We are hamstrung. Russia has 6,300 warheads; the US has 3,750. The deployment of only one would mean an unthinkable, barbaric escalation of the war in Ukraine. We are returning to an agonizing question John Hersey posed in his 1946 masterpiece about the wake of the first atomic bomb, Hiroshima: “The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us an answer to this question?”

We are returning to this territory. To be clear, total nuclear annihilation follows an American strategy. The United States excels at total war, even if we are taught in public schools that it was a German invention. The US killed 112,000 civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; however, we murdered an additional 900,000 in a systemic firebombing campaign of civilian targets. Vladimir Putin is in our Pacific Theater playbook. It is total war. It is meant to pound a country into submission. Civilian casualties are the entire point. He is deliberately targeting civilians to break the will of a people and terrorize the rest of the world into fealty. It’s the American Way.

In public schools, we are taught that the atomic bombs were dropped to “save our boys.” But what about all those firebombs that killed nearly a million civilians? We are also taught that those two atomic weapons were the opening salvo of the Cold War—a way to show the Soviets our dominance in the postwar world—but would we have ever dropped those nuclear weapons on Germany? Or do they look too much “like us”? And, does this sound at all like our hand-wringing about who looks suitably “European” to receive a warm welcome as a refugee? We are in 1939, but with Twitter. The only difference—and it’s a big one—is that we have already seen what nuclear weapons can do. It ratchets up the terror. It’s the same set of total war tactics and, I’ll argue, a piece of the same, ongoing war. (Another neat tie-in: the US government poached over 1,600 Nazi scientists, many of whom directly oversaw death camp labor, torture, and medical experiments, to prosecute the Cold War at NASA, Dow, Monsanto, Lockheed, Boeing, and—wait for it—Disney, among others.)

In researching this book, I was exceptionally moved to learn of Maya Angelou and Malcolm X’s African campaign to bring the United States before the United Nations Human Rights Council to answer for charges of genocide. But no African country would back their efforts because they were receiving Cold War aid money from the US. We have never answered for what we have done to anyone, really: Japan, Vietnam, Central America, Afghanistan, Iraq, indigenous people, enslaved people…The list is terribly long, but the reason is simple: we have never suffered a large-scale invasion or lost a war on our own soil. Rather, we lose post-colonial misadventures where it would have been imprudent to deploy a nuclear weapon.

The US has never suffered like Japan, like Russia, like China, like Africa, like the Middle East, like anywhere in Europe and our inept, arrogant foreign policy telegraphs that fact as loudly as the mortifying statistic that only 20% of Americans are bilingual. And I’d bet a lot of money a good deal of them come from immigrant households. We have no curiosity about the world, yet we control it. We have no experience of the devastation of war, yet we perpetuate it everywhere but at home. Now our world leader status is being held hostage by our own intolerably cruel tactics. We cannot do a damn thing to help those people in Ukraine. But we have the connectivity to watch them die via (privately held) social media.

When I refer to the world we inherited, I use the first person literally. I grew up in the one pause in this arguably eight-decade-long conflict: the delusional 90s. That decade could handily be defined as lasting from the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 to the attacks of September 11, 2001. It was a decade drunk on optimism (cue dancing Bill Gates) if—like everyone in power at the time—you ignored the so-called “Culture Wars” along with the very obvious notion of fallout from the Cold War and took a sweet cruise on the Information Superhighway to a surplus budget. You could triangulate your worries away with Bill Clinton. Don’t ask if the world might still be mired in a state of intractable global conflict, and no one will tell!

Regrettably, the Cold War, which began with the last two bombs of WWII, was not over. Afghanistan was destabilized by a Soviet invasion and a brutal ensuing war. The legacy of that war, combined with a legacy of post-colonial discontent, Cold War regime change, and oil dependency thanks to Eisenhower’s Military-Industrial Complex and the highways it built, sent two planes into the Twin Towers. 9/11 was a wake-up call that worldwide war had never ended, and it featured—for once—US civilian casualties, Americans who woke up one morning and went to work, utterly unaware that they would never come home. The Twin Towers still stand in the Panorama at the Queens Museum—that same pavilion that was a roller skating rink, then the United Nations, then a roller skating rink, once more. Again, we go in circles.

So we look at the world we inherited, again we look at it from New York. We glimpse the panorama. We see the moment that the war came home erased from history where twice we modeled utopia in Queens. Once more, we watch a land war in Europe with economic crashes and a global pandemic in recent memory. New York may well be the world’s capital and it welcomes the world, but it also is the largest city in a country that stubbornly refuses to understand a contemporary world that it has done more than any other existing nation to shape. Once more, we have a Space Race, but, continuing the trajectory of the World’s Fairs, it has cooled from a proxy war in the name of progress to a tepid 15-minute joy ride for oligarchs in a phallic cocoon. The Cold War is often described as a backdrop but it sure has a talent for coming to the fore over and over, a sort of multigenerational landscape.

Russia is still America’s shadow self, a roadmap to US values in that we purport its government to harbor all we deplore. It used to be communism as opposed to the free market and the aforementioned American Way. Today we decry its authoritarianism and its oligarchs—like we don’t have any of our own. We place the evils of the world upon Putin, we pity their people. Putin, like Hitler, actually is conveniently evil. He suits the narrative well. We need our devils, of course, and we need them to be as they are to show why we are good. We must invent the devil to suit our needs. Frankly it’s amazing we haven’t found a new one for 75 years. In fact, he’s up to our own bag of tricks. Dostoyevsky put it best, “I think the devil doesn't exist, but man has created him, he has created him in his own image and likeness.”

This book largely maps the circumstances of my own biography. My family came here and gave me this corner of the world to call mine. Half of them came from Russia, that shadow self. All of them grew up, fell in love, worked, and died on a landscape largely defined by Robert Moses. Character may be fate, but context is everything. I cannot write this essay without mentioning my father, Lou, was born in 1950 in Bushwick, Brooklyn and raised in Levittown, Long Island. (“I’m midcentury!” he once exclaimed in a furniture store.) In Levittown, Lou spent summers biking to Jones Beach; his parents didn’t have much money, but they saved up to see Lenny Bernstein conduct at Lincoln Center, which all of his life he referred to as “going to temple.” Lou attended the World’s Fair over a dozen times.

When my father met my mother (another World’s Fair attendee) through a Jones Beach friend, their Jewish-Catholic marriage was perceived as “mixed”—fittingly with two-thirds of the demographics that Levittown accommodated. Lou taught me about Robert Moses; he spoke of him as a megalomaniac and a racist, to be sure, but he retained an Ahab-like aura that drew my father in. However, just as surely as Lou was a beneficiary of Moses’ infrastructure and had access to the arts and leisure it hosted, as a teenager, he lost his mother to an exceedingly rare tumor. Strange cancers killed nearly everyone in her office, where she did the books for a company that extracted gold from WWII radio equipment through a noxious chemical process. I, in turn, lost Lou to an even rarer tumor. This book is about my inheritance.

This book is a biography of circumstance for my collaborator, too. Half of Johannah’s family is Slovakian and she grew up with relatives on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In her 20s, Johannah became a Fulbright Scholar studying Kazakh textiles in post-Soviet Mongolia. Living in Bayan-Ulgii for a year, she learned firsthand what it was like to be an unintentional foot soldier in soft diplomacy. After a rigorous application process, she fretted about what she would have to do to keep up her end of the bargain. When she arrived, her affiliate university rubber stamped her papers—and she never heard from them again. There was no oversight of her research and, to this day, she wonders if anyone ever read her midway and final reports. At a certain point, it dawned on her: it was her presence that mattered more.

During her time with Mongolia, she saw the same thing with the Peace Corps. Her peers had the correct intentions, but no resources to carry them out. Logistically they were supported, and given a schedule of vaccines so vast that it included an anti-bubonic plague shot—in case of a freak marmot bite. However, any programs the volunteers wished to start received no funding. One woman in Johannah’s cohort wanted to supply a local area with sports equipment for a school: she had to fundraise for it herself in the US. Another man arrived and was assigned to a children’s enrichment program at a local community center—that didn’t exist. No one had an alternate plan for him, so he helped out in odd ways that he could. Ultimately, it was their presence that was the point. While Johannah will eagerly tell anyone that the Fulbright changed her life and her career—she doubts she had any impact whatsoever on Mongolia. The veil was pulled back and she knows why she was there. This book is about her inheritance, too.

I write as I turn 40, halfway through it all if those Equitable Life tabulators are to be believed—far more than halfway through it if those wacky Long Island Expressway tumors are part of my inheritance, too. I write it in Manhattan, a few blocks from Moses’ West Side Highway, as a child who was a religious attendee at Lincoln Center’s Young People Concerts, and with a father who instilled in me an abiding love of City and State beaches. Six weeks after I was born, EPCOT opened; I went when I was only a few months old, and on many family vacations after that. At some point in researching this book I realized I have, in fact, been to the World’s Fair. I inherited those hopes for “A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow.” I took all the rides.

As I fear that perhaps I have been taken for a ride and spent an entire childhood high on corporate futurism, I come back to another cultural artifact of my youth: Paul Simon. The Flushing native released Graceland on my fifth birthday, and I went with Lou to Tower Records to buy it on vinyl, cassette tape, eight-track, and CD. The album’s first track contains the lyric, “These are the days of lasers in the jungle/ Lasers in the jungle somewhere.” When I called my father’s best friend from high school to ask him what it was like to go to the World’s Fair over a dozen times with my father, Bill told me that Lou laughed hysterically at the depiction of lasers cutting down trees in General Motors’ Futurama. He laughed every time that they went. Lou couldn’t believe that this was supposed to be a positive vision of the future. It cracked him up.

Bill, a horticulturalist, also told me about a recent hike he took around the World’s Fair grounds with his partner, who incidentally collects World’s Fair memorabilia. Each year, they go to pick cherries, which he tells me are exquisite. As they did so last year, Bill realized that, aside from the trees that had been planted by the World’s Fair landscape architects, he was also in the midst of Katsura trees, native to East Asia. When he looked up the map of the World’s Fair pavilions, he noted that he was standing where South Korea’s had been. The seeds remained and rose up through the soil. The lasers in the jungle had not prevailed, after all.

—Cara Marsh Sheffler

“Over everything—up through the wreckage of the city, in gutters, along the riverbanks, tangled among tiles and tin roofing, climbing on charred tree trunks—was a blanket of fresh, vivid, lush, optimistic green; the verdancy rose even from the foundations of ruined houses. Weeds already hid the ashes, and wild flowers were in bloom among the city’s bones. The bomb had not only left the underground organs of the plants intact; it had stimulated them.”

―John Hersey, Hiroshima

“For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease.”

—Job 14:7